-

Harrison Theater

-

Earl's Sandwich Shop

-

Sunday School Group

Outside of Reid's Pharmacy

-

True Reformers Hall

-

Earl's Sandwich Shop

At Fifth and Polk

-

New Era Building

-

Golden Tavern

-

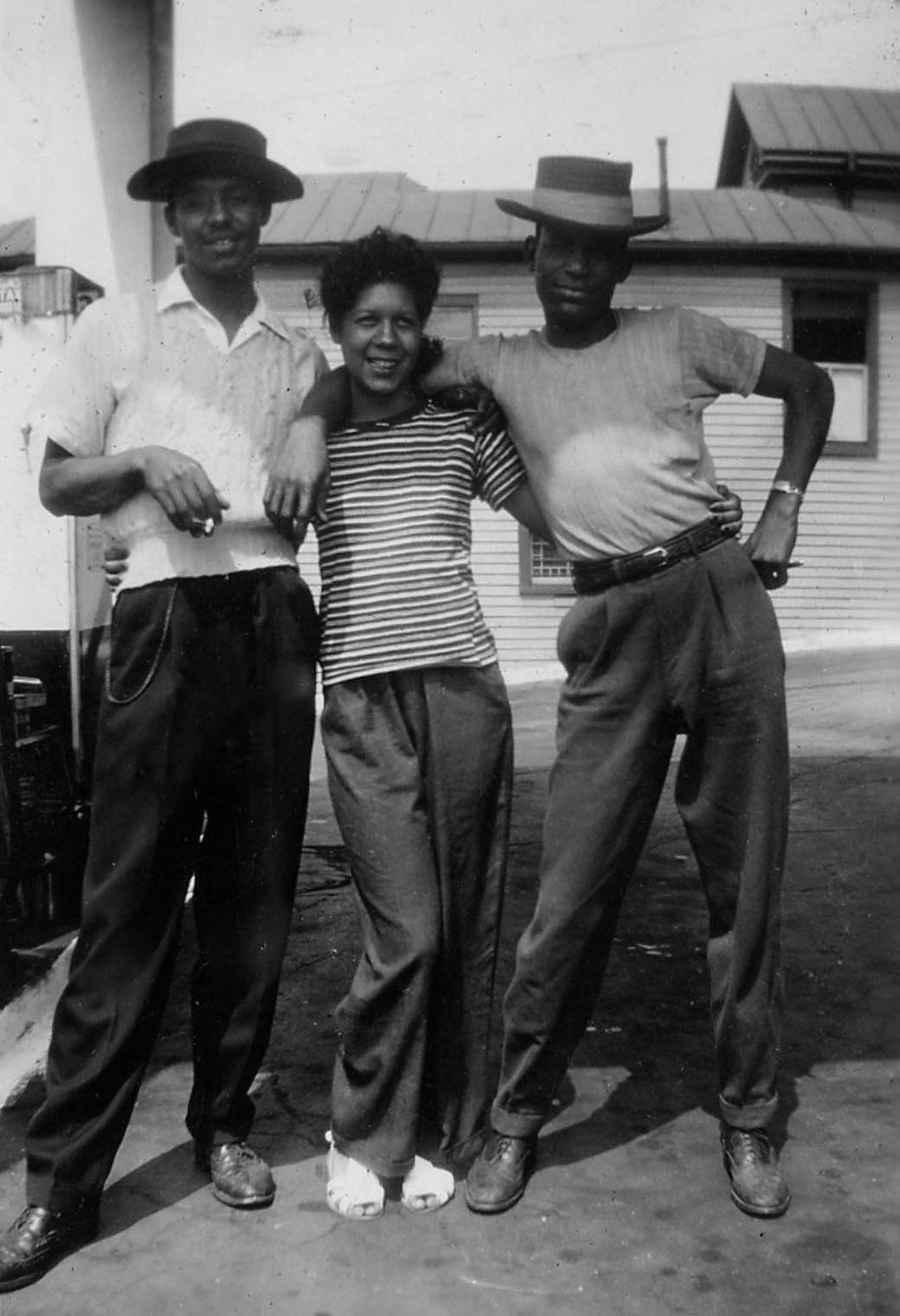

Hanging out, 1940s

Isaiah Volley, Majurial “Juicy” Crawley, and Walter C. Tweedy near the gas station at Fifth and Monroe.

Fifth Street was the social center of African American life in Central Virginia for decades. Black fraternal orders and lodges—the Prince Hall Masons before the Civil War, the Independent Order of St. Luke, the True Reformers, and the Odd Fellows shortly thereafter—laid the foundation for social activities that provided African Americans with comradeship, entertainment, and a sense of belonging. Fraternal orders and businesses supported each other. The Odd Fellows met on the second floor of the Kentucky Hotel; the Masons used upstairs space at the C.V. Wilson Funeral Home. The Elks, established in 1913, began meeting at 1014 Fifth, near the corner of Monroe, as early as 1924, in an office-and-assembly space. Especially in the first half of the 20th century, Fifth Street was where Central Virginia’s African Americans gathered to “let the good times roll.”

An African-American Commercial & Cultural Center

show more

Following the Civil War, African Americans realized new opportunities as well as limitations. While amendments to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and granted citizenship to African Americans, a new system of racial discrimination, known as “Jim Crow,” soon emerged. The majority-controlled society denied African Americans access to respectable jobs and many commercial services, and African Americans formed parallel economies in their own communities.

During the late 1880s, most of Fifth Street was predominately occupied by white residents or business owners. The 400, 600, and 900 blocks had close to twenty percent African American occupancy, while the 1000 block and beyond was generally occupied by a black majority. By 1900, the percentage of African American residents began to increase somewhat, particularly along the 900 block of Fifth Street. By 1910, an African American-dominated business district had evolved in the three block area between Federal and Monroe Streets. Black business owners may have obtained a foothold in the district due to opportunities created by a weak economy in the early years of reconstruction, but the African American business community’s rise to prominence was not simply due to passive acceptance of what may have been considered undesirable property by the white business community. Rather, several successful black business leaders, along with newly-formed fraternal and social organizations, made significant investments in the corridor by constructing a number of large commercial buildings in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The vanguard of these black business owners included boot and shoe makers Pitman Walker and James Ross, grocer Nelson James, and barber J.O. Ross, who were all operating in the 1000 block of Fifth Street as early as 1881.

During this time, many black fraternal organizations were formed, “creating social outlets for those seeking camaraderie as well as a sense of belonging in the face of a larger society that neglected them.” These groups promoted the concept of “self-help,” and played a key role in development of a black middle class in southern cities like Lynchburg.

By 1872, African American men in Lynchburg formed a local chapter of the Order of True Reformers, a fraternal organization. In 1893, they constructed the landmark building known as the True Reformers Hall (later known as the Harrison Theatre) in the 900 block of Fifth Street on the site of Pleasant Partin’s tobacco factory. Perhaps the first “mixed use” building on Fifth Street, the massive three-story edifice contained a large auditorium, offices, a lodge hall for the True Reformers, and several storefronts at street level. Perhaps as important for its cultural, social, and commercial contribution to the district as its architecture, the True Reformers Hall was demolished in 1985.

On March 5, 1918, a group of African American women rented the house at 613 Monroe Street (118-5318-0061) in order to begin Y.W.C.A. programs for women of color. Soon after, Adela Ruffin, Field Secretary for all black Y.W.C.A. participants in the South, came to Lynchburg to encourage local leadership to create a separate chapter, but her suggestion was tabled. In 1919, however, an official Phyllis Wheatley Branch was formed in Lynchburg, and 15 African American women established a Committee of Management. The Central Association (white-controlled organization), located on Church Street, offered to help the Phyllis Wheatley Branch in “any way that it could, but was unable to assist financially.” In 1924, the trustees of the Old Dominion Elks Lodge #181, who had purchased 613 Monroe from the Merchants National Bank of Raleigh in 1919, sold the house to the Y.W.C.A. for $4,000.

In 1937, it was reported that the branch had outgrown their building at 613 Monroe, and that a committee had been formed to evaluate their options. While the branch had saved money for renovations through the years, they would also need to obtain support from the community. Amy Jordan, a teacher at a “colored college” (Virginia Theological Seminary) was the chairman of the Committee of Management, and Grace Booker, a native of Columbus, Ohio, was Executive Secretary of the branch. Later, Booker became the first African American Director of the Metropolitan Y.W.C.A. in Baltimore.

An undated brochure produced by the Phyllis Wheatley Y.W.C.A. sought to raise $45,000 for the purpose of moving the branch from its house at 613 Monroe Street, which was labeled as “Old—Outgrown” to a larger building at 600 Monroe Street, which was labeled “Modern—Adequate.” 600 Monroe Street was known as the “Tal-Fred Apartments” (118-5318-0060), and was built circa 1940 on property formerly occupied by the Independent Order of St. Luke. The newly-constructed apartment building appears to have contained six spacious units, all of which were occupied by African Americans. The Phyllis Wheatley Branch apparently raised the necessary funds to acquire the property, and hired prominent Lynchburg architect Pendleton S. Clark to plan modifications to the building’s interior. The Y.W.C.A. branch moved into the building by 1950, and it is still owned by the organization today. The Y.W.C.A. program in Lynchburg was integrated in the early 1970s.

In 1924, the house at 1014 Fifth Street (118-5318-0049) was occupied by the Elks Rest, a facility for African Americans. In 1936, Willis Sandidge was the manager of the Elks Rest, and Old Dominion Lodge #181, IBPOE (Elks) used the building as its principal office and meeting location. In need of additional assembly space, the organization added a large concrete masonry unit addition to the rear of the building by 1951, and the grocery store operated by James Harper and later Robert Miller at 1016 Fifth Street was incorporated into the Elks Lodge complex.

For most of the first half of the 20th century, the Kentucky Hotel (118-0177) at 900 Fifth Street served as the Odd Fellows Hall, with rental office space on the first floor and the second floor contained the lodge hall itself. In 1954, the building housed the Grand Order of the Odd Fellows, Odd Fellows Lodge No. 1475, St. Luke’s Lodge No. 1475, Sons of Zion Lodge No. 1446, and West Hill Lodge No. 1704.

By 1962, the Augustine Leftwich House at 614 Federal Street (118-5318-0063) began a new life as the “Masonic Home.” Joseph C. Watson resided at the house (perhaps as a manager or caretaker) and the building housed the Star of the West Lodge No. 24 (AF&AM), Order of the Eastern Star Lynchburg Chapter No. 40, and Order of the Eastern Star Goodwill Chapter No. 125 (all of these were African American organizations). The building at 614 Federal Street continues to serve the Star of the West Lodge today.

The Lynchburg Branch of the N.A.A.C.P. (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) sponsored the Legacy Project to provide educational exhibits and programs on the history and culture of African Americans in the area. The Legacy Project received 501(c)3 nonprofit status in 1995 and acquired a dilapidated house at 403 Monroe Street two years later. Lynchburg architect Kelvin Moore was engaged to help transform the 100-year-old house into a modern museum. A Capital Fundraising Committee was formed to raise $300,000, and a Collections Committee was formed to solicit and archive artifacts for the permanent collection. On June 25, 2000 a celebratory dedication and grand opening was held, and the Legacy Museum of African American History hosts a number of changing exhibits about black culture in the region.

show less