-

Franklin Coal company

In the 1890s, John Franklin Sr. owned this fuel company, located at 1013 Fifth.

-

Fifth Street, east side, mid-1950s

Bill’s Pastry Shop, TV Repair, and Portsmouth Fish Market

-

Southern Air, mid-1950s

-

African American Businesses

In the 800 block of Fifth between the Roundabout and Jackson were a doctor’s office, a funeral home and lodge, a private residence, and a dentist’s office.

-

Hutcherson’s Funeral Home, 1939

The original Hutcherson’s building

-

Strange and Higginbotham Funeral Home, 1947

Strange and Higginbotham was one of the first businesses to provide professional mortuary services in Lynchburg.

-

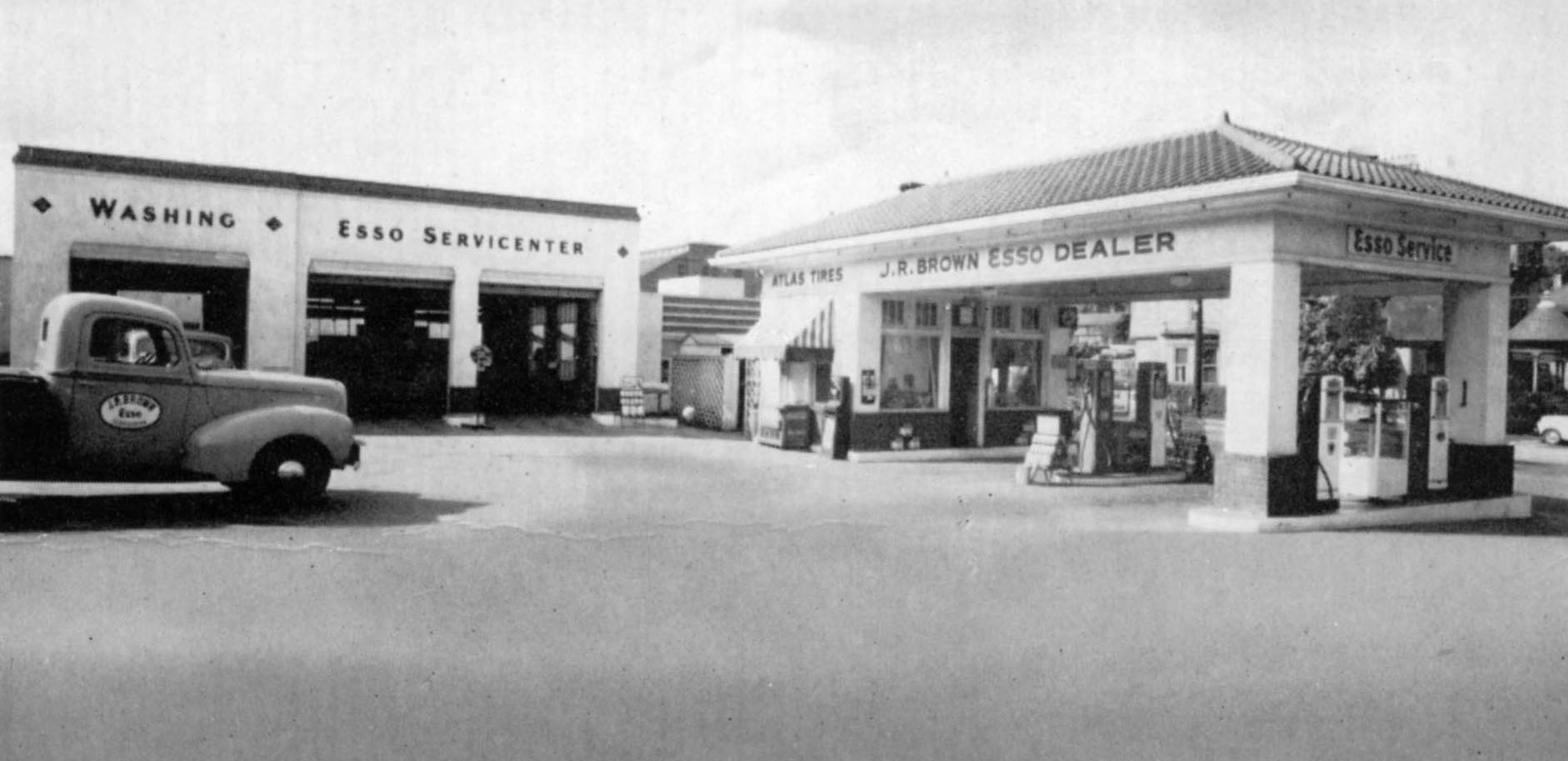

J.R. Brown Esso Dealer, mid-1950s

At the corner of Fifth and Federal at the Roundabout, the building that housed this full-service gas station remains in service today.

-

New Tread Company, 1940s

Built in1927 and occupied by several automotive businesses, this building still stands at the corner of Fifth and Court.

-

Hoskins Pontiac Company, 1940s

This automobile showroom still stands on the west side of Fifth at Monroe.

-

Adams Motor Company, 1950s

An automobile showroom constructed in 1927, this building housed three different motor companies before being sold in 1930 to the Adams Motor Company.

-

Gulf Station and Bibee Grocery, 1940s

At north corner of 5th and Federal

In the decades just before and after 1900, the blocks between Madison and Federal streets boasted 18 businesses —including a carriage works, greengrocer, shoemaker, blacksmith, barbershop, saloon, butcher shop, fish market, and woodworking shop—as well as a few residences. Fifth Street has been a business district from its earliest days as Lynchburg’s heavily traveled western thoroughfare. In the early 19th century, grocers, sellers of dry goods and ready-made clothing, and other retailers catered to travelers along the busy road. Fifth Street, like downtown Lynchburg, suffered a decline with the building of shopping centers farther away from the center of town. Both Pittmann Plaza, completed in 1960, and the River Ridge Mall, which opened in the early 1980s, drew business away from the older downtown and Fifth Street areas.

Business and Industry

show more

In 1883, a new city fire station was constructed at 514 Fifth Street (118-5318-0011). “Fire Station No. 1,” which boasted 15 men, 1 steam engine (pulled by 4 horses), 1 hose wagon (pulled by 2 horses), and 1 hook and ladder (pulled by 4 horses), served for more than four decades before being supplanted by a new Art Deco style facility designed by Clark and Crowe at the intersection of Fifth and Church Streets (demolished).

Biggers School (called the “Fifth Avenue Public School” in 1890), located at the west corner of Clay and Fifth Streets, opened in 1881 with a capacity of 305 students. The large building was designed by August Forsberg, and was demolished in 1967. Except for the school and the Gist, Bruce, and Halsey tobacco facilities, the “lower” end of Fifth Street (the 200-400 blocks) was primarily residential in nature during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The 500 block contained a bakery & confectionary, two grocery stores, an ice cream parlor and dairy, a drug store, the Lynchburg Steam Laundry, and the newly-constructed Fifth Street Fire Station (118-5318-0011), which was labeled “Fire Station No. 1.” The 600 and 700 blocks of Fifth Street boasted 18 stores, a restaurant, wood working shop, and the former Phoenix Carriage Works at Fifth and Federal. Three of these stores remain, including the early 19th century buildings at 612 and 708 Fifth (118-5318-0018 and 118-5318-0027, respectively) and the circa 1850 brick building at 620 Fifth Street (118-5318-0021). The 900 and 1000 blocks of Fifth Street contained six grocery stores (including R.H. Padgett’s store, which occupied an ancient c. 1800 store at the corner of Polk and Fifth that was demolished in the mid-20th century), two shoe stores, a candy store, a barber, and two tobacco factories (J.B. Evans & Son and Loyd Phelps & Co.).

By the end of the first quarter of the 20th century, the automobile had firmly taken hold in Lynchburg, and the burgeoning city was even home to the Piedmont Motor Car Company, one of only two companies in Virginia that actually manufactured automobiles (this factory was located just over a mile northwest of Fifth Street). New businesses were needed to serve the needs of the now-ubiquitous machines, and gas stations, tire stores, and other establishments began to spring up all over town. Some of the first auto-oriented development that took place along Fifth Street occurred in the previously-residential 400 block. In 1928, the city directory announced that 400 Fifth Street was occupied by the Miller Tire & Battery Company, while the Lynchburg Battery & Ignition Company was located at 406 Fifth Street (both buildings are now joined, and are designated as 118-5317). Ferdinand D. Miller was the proprietor of Miller Tire & Battery at 406 Fifth Street, which sold Hood Tires and Willard Batteries. By 1935, the building was home to Goodyear Service Automobile Tires under the management of Oliver E. Miles. By 1940, the business was being operated under the name of “New Tread Company Vulcanizing” by D. Earl Burnett. The business specialized in recapping, retreading, and vulcanizing tires, and was a distributor for the U.S. Tire Company. Burnett purchased the building from E.H. Hancock in 1943, and was operating the Burnett-Benson Tire Company on the site by 1945. In addition to U.S. Tires, the business sold Seiberling Tires, radios, sporting goods, and home appliances. A 1945 advertisement boasted that they were the “most comprehensive tire service in Lynchburg.” By 1955, Burnett-Benson Tire Company had been renamed to simply Burnett Tire Company, and the firm was selling aircraft parts in addition to their automotive parts and accessories. The next year, the company commissioned the architectural firm of Cress & Johnson to design a modern, streamlined facility across the street at what would become 403 Fifth Street (118-5318-0004).

Also in 1927, the automobile showroom at 811 Fifth Street (118-5318-0034) was constructed to house three separate motor companies owned by Myers, Beasley, and Phil Payne. In the 1930s, the building was acquired by Adams Motor Company, which sold cars at the location through the end of the 20th century. The automobile dealership at 407 Federal Street (118-5237) was constructed in 1937 for the Pyramid Motor Corporation, which sold Ford and Lincoln Zephyr automobiles. After 1948, the business changed hands and was called Turner Buick Corporation. The name then changed to Dickerson Buick Corporation in 1955 and to Hemphill Buick-Opel, Inc. in 1970. The building was acquired by the Sheltered Workshop of Lynchburg in 1975, and was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.

Other purpose-built automobile-oriented commercial buildings in the district include filling stations at 1100 Fifth (118-5318-0051) and 801 Fifth (118-5318-0032), the Hoskins Pontiac Company showroom at 1101 Fifth (118-5318-0052), and the garages at 619 Fifth (118-5318-0020), 420 Monroe (118-5318-0056), and 507 Harrison Street (118-5318-0022).

In 1930, the Lynchburg firm of Johnson and Brannan designed a new bus terminal at the intersection of Fifth and Church Streets for A.F. Young, operator of the nearby Virginian Hotel at 726 Church Street (118-5163-0076). This Greyhound depot (demolished) was the first of two such facilities constructed along Fifth Street, which was part of Lynchburg’s primary north-south transportation network. In 1953, a Trailways bus station was constructed at 512 Fifth Street (118-5318-0010). Several residential and commercial buildings along Fifth Street were demolished to make room for the station, and in 1962, the building became known as the Union Bus Station, serving both Trailways and Greyhound passengers. At this time, additional houses along Clay and Madison Streets were demolished to provide larger parking areas. According to Greyhound officials, this instance was the first time (in company history) that the two bus lines had shared a single facility.

In 1931, Fifth Street was designated as U.S. Highway 29, which connected Maryland to Florida. Following the construction of the Lynchburg Expressway, Fifth Street was redesignated as U.S. 29’s business route. While long-distance traffic may have decreased, local traffic was on the rise as Lynchburg grew and the Fifth Street corridor found itself between downtown and the midtown area, which contained Pittman Plaza (Lynchburg’s first shopping center), which was completed in 1960. To increase traffic flow, on-street parking was removed from Fifth Street in order to create two lanes of southbound traffic. In the early 1970s, the Virginia Department of Transportation developed a plan to further increase traffic flow through the area by turning Fourth Street (a narrow residential neighborhood-serving roadway) into a one-way thoroughfare for vehicular traffic, while converting Fifth Street to all one-way in the opposite direction. This plan, along with the assumed significant right-of-way acquisitions that would need to be made in order to enact it, had a chilling effect on any reinvestment that might have otherwise occurred along Fifth Street. Like downtown Lynchburg (and most other downtowns during the 1970s), the Fifth Street commercial district suffered a decline due to large shopping areas including Pittman Plaza and River Ridge Mall, which opened in the early 1980s.

The African American population in Lynchburg was on the decline by the late 19th century, largely due to the reduction of employees needed in the various tobacco warehouses and factories in the city, which were major employers of blacks. Newer industries in the area, including cotton mills and shoe factories, only employed white laborers (due to necessity if for no other reason, many of these companies would later employ blacks). Despite the reduced role that tobacco played in Lynchburg’s economy, the Stalling & Company tobacco factory, which occupied the former Myers building at Fourth and Federal Streets, employed area residents well into the 20th century. James B. Harvey (1928-1984) worked at the Stallings Factory in the 1950s. His son, Richard, later wrote that he “went to visit my father once at the Tobacco Factory on Fourth Street…His boss cursed and talked to him as if he was less than a dog. I swore, not one time in my life, would I be subjected to this bigotry.” Dubois Miller worked at the factory one summer, and he later recounted that he would “come home smelling like tobacco, and I didn’t smoke, so I didn’t appreciate it. But I needed the money for school, and it was seasonal work.” The G. Stalling & Co. Factory was destroyed by fire in 1976.

As educational and economic opportunities for African Americans increased, entrepreneurism also increased. In 1904, Lynchburg’s black population operated 2 billiard saloons, 2 theatres, and 2 livery stables. There were 3 African American physicians or veterinary surgeons, 3 undertakers, 2 attorneys, 5 hucksters (street vendors), 1 plumber, 1 electrical contractor, 1 chiropodist, 23 barbers, 27 merchants, and 32 houses of private entertainment (private lodging facilities that did not serve alcohol) .. Thus, to some extent, the black community began to mitigate the effects of segregation in the industrial workplace with their own business opportunities, many of which operated on Fifth Street (or Fifth Avenue, as it was sometimes called during this period).

By 1900, the Kentucky Hotel (118-0177), a former tavern and residence, was the home to Smith’s Business College, which provided educational opportunities to African Americans. Its students included Rev. George Robert Jones of Suffolk, who graduated in 1897. An 1899 advertisement in the Richmond Planet announced that the school offered courses in “phonographic, penning, commercial, English…”, and a 1908 publication lauded T. Parker Smith, the school’s director, as “one of the pioneers” in the work of training African Americans in the principles of business. Smith, a Missouri native who graduated from Lincoln University in 1888, married Clara Alexander of Lynchburg. By 1911, they had moved to Durham, North Carolina, where he was the Dean of the Commercial Department at the National Religious Training School, and Clara served as the head of the Teacher’s Department. By 1934, Smith was operating a new Smith’s Business College in Kansas City, Missouri.

In 1915, local African American businessman Adolphus Humbles (1845-1926) built what is known as the Humbles Building (118-5318-0039) at 901 Fifth Street. Like the True Reformers Hall, the Humbles Building is a large, three-story, mixed use facility that contained two storefronts on the first floor and an auditorium on the second floor. Humbles was a successful merchant in Campbell County, and operated the toll road between Lynchburg and Rustburg (the seat of Campbell County). He served as the Treasurer of both the Virginia State Baptist Convention and the Virginia Theological Seminary and College (now known as the Virginia University of Lynchburg), where the school’s main building bears his name. Also active in politics, he served as Chairman of the Campbell County Executive Committee for the Republican Party for thirteen years.

In 1919, the former Gist Tobacco Factory at 410 Court Street (118-0075) was converted into Mill No. 2 of the Lynchburg Hosiery Mills Company (Mill No. 1 [118-0126] was on Fort Avenue), which had the specific purpose of employing African American women. At the time, it was said that no other business or industry in Lynchburg had hired black women, who, up until this point, were limited to performing domestic work in white households. Mill No. 2 operated until 1971, and generally employed between 150 and 200 black women at any given time. As at Mill No. 1, the segregated employees of Mill No. 2 formed a “Lynchburg Hosiery Mills Association,” which provided benefits including an early form of medical insurance, disability benefits, unemployment benefits, and savings plans. When the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964, the two separate Lynchburg Hosiery Mill Associations were merged, and both black and white employees then belonged to the same association.

As previously mentioned, three African American undertakers were in business in Lynchburg at the turn of the century. John Shuemaker & Co. operated at 417 Monroe Street, and was a former partner with Squire Higginbotham. Their funeral home, established in 1868, is thought to be the oldest black business of the type in Lynchburg. Squire’s son, McGustavus (1868-1934), owned the firm of Strange & Higginbotham, which was located at 909 Fifth Street (118-5318-0040). This business was the predecessor to the current Community Funeral Home, which was established by M.W. “Teedy” Thornhill, Jr. Thornhill served on Lynchburg City Council from 1976 to 1992, and in 1990, was elected as Lynchburg’s first African American mayor. C.V. Wilson’s Funeral Home was located at 810 Fifth Street, but was demolished in 1968 to make additional car lot space for Adams Motor Company. Carl Hutcherson, Sr. erected a new funeral home at 918 Fifth Street (118-5318-0042) in 1963. Hutcherson was the first African American to serve on the Lynchburg School Board, and his son, the Rev. Carl B. Hutcherson, Jr., took over the mortuary business, served on Lynchburg City Council from 1996 to 2006 (he was Mayor from 2000 to 2006).

show less